Today, spices are everyday kitchen staples—pinches of cinnamon in oatmeal, a dash of black pepper over eggs, turmeric stirred into a latte. But in the ancient world, these same powders and seeds carried meanings far beyond cooking. Spices were sacred, mythic, and world-shaping. They drove economies, sparked exploration, flavored the banquets of kings, and perfumed the breath of emperors.

In myths and legends, they grew in lands guarded by serpents or giant birds, gifted by gods, or holding the secret of eternal life. In reality, they were precious cargo that crossed deserts and seas, linking cultures long before globalization had a name.

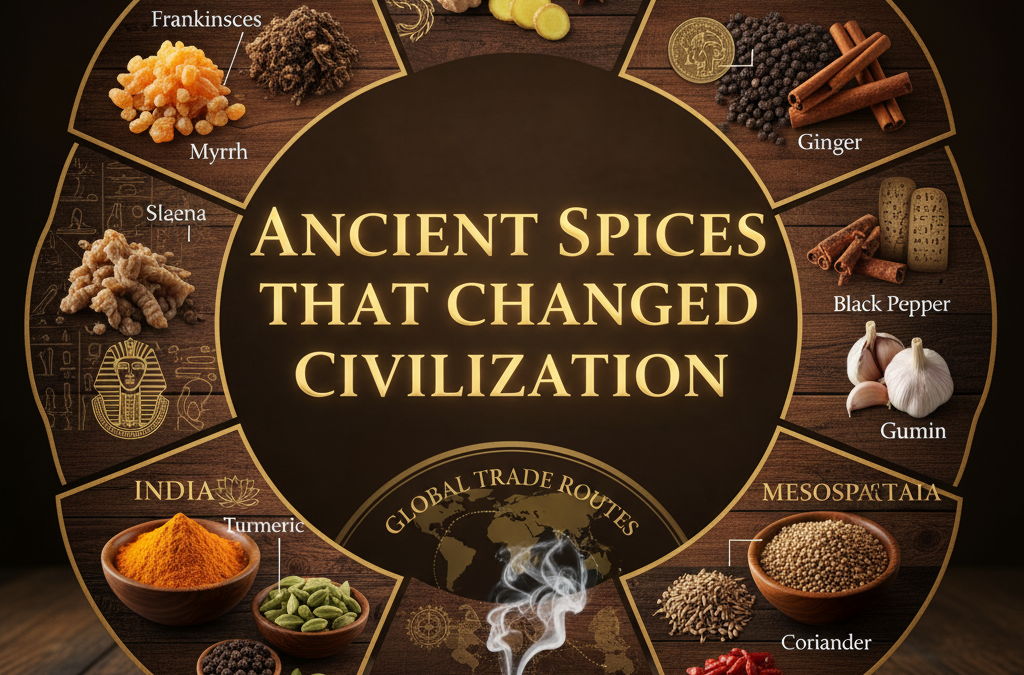

Spices didn’t just change diets—they changed civilization itself.

Egypt: Spices of Life and Death

The Egyptians revered spices as tools of both ritual and eternity. Archaeologists have discovered traces of cinnamon and cassia in the wrappings of mummies, though these spices had to travel thousands of miles from South Asia. For Egyptians, spices were not just luxuries—they were keys to immortality.

Frankincense and myrrh, resins burned in sacred ceremonies, carried powerful mythic associations. Frankincense was believed to be the “sweat of the gods,” its smoke rising heavenward like divine breath. Myrrh was sacred to Isis, the goddess of magic and rebirth, and was believed to guard souls in their passage to the afterlife.

The legend of Queen Hatshepsut’s expedition to the Land of Punt adds to the spice’s mythic aura. Returning ships carried exotic trees said to be gifts from the gods themselves. The scent of incense was more than fragrance—it was the promise of eternity, a fragrant bridge between mortals and the divine.

India: Healing, Myth, and Cosmic Order

India was both birthplace and spiritual home to many of the world’s most influential spices: pepper, turmeric, cardamom, ginger.

The Atharva Veda, a sacred text dating to the 1st millennium BCE, praises pepper not only as food but as medicine and protection against evil. Turmeric was woven into ritual and mythology—painted on brides for fertility, used in offerings to Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity, and praised for its “golden” power to purify.

Cardamom, called the “queen of spices,” was said in some traditions to grow in the gardens of Kubera, god of wealth. Eating it wasn’t just indulgence—it was tasting a fragment of heavenly abundance.

Spices in India weren’t merely trade goods—they were threads of dharma, tying human health, ritual purity, and cosmic balance into one fragrant whole.

Mesopotamia: Everyday Magic of Garlic and Cumin

In Mesopotamia, the cradle of cities, spices appear in some of the world’s oldest recipes. Clay tablets detail stews seasoned with garlic, cumin, and coriander. Yet these were not only culinary tools—they carried protective and sacred power.

Garlic was considered a talisman against evil spirits, its pungent bite a kind of invisible shield. Cumin and coriander seeds were linked to fertility rites and sacrificial offerings.

Legends mingled with practice: in hymns to Ninkasi, goddess of beer, spiced and fermented drinks were not mere refreshment but bridges to the divine. Spices flavored feasts that blurred the line between banquet and ritual.

Rome: Pepper, Serpents, and Cinnamon Birds

By the time of Rome, spices had become luxuries of empire, their origins wrapped in myth. Pepper—imported at enormous expense from India—was said to grow in lands crawling with venomous serpents. To harvest it, locals supposedly set fires to drive the snakes away, a myth that gave pepper both its smoky scent and its danger.

Cinnamon, too, was veiled in legend. Pliny the Elder wrote that it grew in nests of giant birds perched high in the mountains. Traders tricked the birds by laying out chunks of meat; when the birds carried the heavy offerings back to their nests, the branches collapsed, dropping cinnamon down for collection.

Whether or not anyone believed these tales literally, they served a purpose: they reinforced the sense that spices were otherworldly, perilous, and priceless. To eat them was to consume something almost magical.

China: Aromatics of Immortality

In ancient China, spices and aromatics were deeply tied to medicine, alchemy, and myth. Cinnamon (cassia) was prized as an elixir of long life, while ginger was believed to “warm the stomach and drive out demons.”

Daoist traditions told of sacred mountains where mystical herbs and fragrant spices grew—ingredients in the Mushrooms of Immortality sought by emperors. The Yellow Emperor, a semi-mythical figure, was said to have dispatched envoys to distant seas in search of such eternal flavor.

One particularly vivid story surrounded cloves. During the Han dynasty, courtiers who wished to address the emperor were required to chew cloves beforehand, ensuring their breath was fragrant in his presence. Over time, cloves became not just breath-fresheners but symbols of loyalty and purity.

Sacred Fires, Holy Smoke

Across the ancient world, spices often carried their power not in cooking pots but in fire and incense.

- In Judaism, frankincense was burned in the Temple of Jerusalem as a symbol of prayers rising to heaven.

- In Christianity, frankincense and myrrh were gifts of the Magi to the infant Jesus, representing divinity, sacrifice, and eternal life.

- In Buddhism, sandalwood incense created a fragrant atmosphere for meditation, guiding the soul toward enlightenment.

Burning spices released not just aroma but meaning—an invisible bridge between mortals and the divine.

Why Spices Mattered

From a practical standpoint, spices also carried concrete value. Their antimicrobial properties preserved foods; their healing qualities made them invaluable in medicine. But their rarity, their distance from the lands of consumption, and the myths surrounding their origins gave them a symbolic weight far beyond utility.

They represented:

- Power: Kings and emperors monopolized them.

- Wealth: Caravans and fleets were financed to acquire them.

- Mystery: Myths ensured their sources stayed hidden, preserving high prices.

- Sacredness: Their smoke, taste, and scent were woven into ritual life.

Spices were the ancient world’s most portable magic.

Conclusion: Spices as Myth, Memory, and Civilization

In the ancient world, spices were never “just food.” They were legends made edible. Egyptians embalmed with cinnamon to borrow eternity. Indians offered turmeric to the gods to invoke prosperity. Mesopotamians flavored their beer with garlic and coriander in honor of deities. Romans spun wild tales of cinnamon birds and serpent-guarded pepper. Chinese emperors demanded cloves as tokens of respect and sought cinnamon as a path to immortality.

Each spice carried both story and substance—healing properties alongside myth, economic power alongside sacred symbolism.

To taste a spice was to taste the world: the sweat of gods, the breath of emperors, the smoke of sacrifice, the wealth of distant lands.

Spices didn’t just season civilization. They flavored its myths, its rituals, and its very sense of the divine.

Even now, when you pinch cinnamon into your coffee or grind pepper onto dinner, you are brushing against that same ancient magic—whispers of myths, caravans, temples, and stories that forever changed the course of human history.